|

THE DHARMA FLOWER SUTRA (Lotus Sutra) SEEN THROUGH THE ORAL TRANSMISSION OF NICHIREN DAISHŌNIN The First and Introductory Chapter

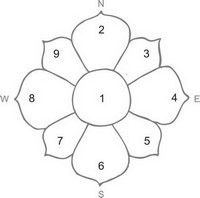

Nam Myōhō Renge Kyō The Oral Transmission on the Meaning of the Dharma Flower Sutra (Ongi Kuden) states that Namu is a word that comes from Sanskrit (Namas); here, when rendered into Chinese, it means “upon what we devote and establish our lives”. The Object of Veneration (gohonzon), whereupon we establish our lives and to which we devote them, is both the person of Nichiren and the Dharma, which is characterised by the one instant of thought containing three thousand existential spaces. The person is the Eternal Shākyamuni who is contained within the text of the Sutra on the White Lotus Flower-like Mechanism of the Utterness of the Dharma (Myōhō Renge Kyō). The Dharma is the Sutra on the White Lotus Flower-like Mechanism of the Utterness of the Dharma (Myōhō Renge Kyō) as the recitation of its title and subject matter [the daimoku, which is Nam Myōhō Renge Kyō] and its Fundamental Object of Veneration (gohonzon), both of which we dedicate our lives to and establish them on. Again, devotion means to turn to the principle of the eternally unchanging, indispensable quality of existence (fuhen shinnyo) [the fixed principle of the true nature of existence], as it was expounded in the teachings derived from the external events of Shākyamuni’s life and work (shakumon). The establishment of one’s life means that it is founded on the wisdom of the original archetypal state (honmon), which is reality as it changes according to karmic circumstances (zuien shinnyo). We in fact establish our lives on and devote them to Nam Myōhō Renge Kyō, which means to devote our lives to and found them on (Nam[u]) the Utterness of the Dharma [entirety of existence, enlightenment and unenlightenment] (Myōhō) permeated by the underlying white lotus flower-like mechanism of the interdependence of cause, concomitancy and effect (Renge) in its whereabouts of the ten [psychological] realms of dharmas [which is every possible psychological wavelength] (Kyō). There is an explanation by the Universal Teacher Dengyō (Dengyō Daishi), who states, “. . . . both the wisdom of the teachings of the original archetypal state (honmon), which implies reality as it changes according to karmic circumstances (zuien shinnyo), and the principle of the eternally unchanging, indispensable quality of existence at the same time (fuhen shinnyo) [the fixed principle of the true nature of existence], as it was expounded in the teachings derived from the external events of Shākyamuni’s life and work (shakumon) . . . . .” This refers to the silence and the shining light that are in fact the real and fundamental nature of life itself. Also, devotion is the manifestation of our physical selves, whereas establishing our lives on something is a dharma of the mind. The ultimate teaching of the Sutra on the White Lotus Flower-like Mechanism of the Utterness of the Dharma (Myōhō Renge Kyō) points out that both mind and materiality are not separate from each other. There is an explanation that says, “We take refuge in this ultimate teaching [i.e., the Dharma Flower Sutra (Hokke-kyō)], because it is the vehicle to enlightenment that the Buddha himself relied on.” The Oral Transmission on the Meaning of the Dharma Flower Sutra (Ongi Kuden) then goes on to say that the Nam(u) of Nam Myōhō Renge Kyō is derived from Sanskrit (Namas) and that myōhō, renge, and kyō are words of Chinese origin. This makes Nam(u) Myōhō Renge Kyō both Sanskrit and Chinese at the same time. [At the time of the Daishōnin these two languages were the main tongues of humankind.] Also Myōhō Renge Kyō is in Sanskrit Saddharma Pundarîka Sutram. Sad [the phonetic change of Sat] is Utterness in English and Myō in Japanese. The nine ideograms that are a substitute for the Sanskrit lettering are the five Buddhas and four bodhisattva entities on the eight petals and the centre of the lotus flower that lies in the breast of all sentient beings. [This eight-petalled lotus with five Buddhas (one in the centre) and four bodhisattva entities is a Shingon or Tantric concept that is the central court of the mandala that represents the underlying Buddha nature that runs through the whole of both physical and mental existence.] This concept implies that the nine realms of dharmas of ordinary existence are not separate from the oneness of the enlightened realm of the Buddha. Myō or Utterness is the Dharma realm or enlightenment, which is Nam Myōhō Renge Kyō and all its implications. [This is the real nature and the original state of the world of phenomena (the content of the Buddha enlightenment being a full understanding of what dharmas really are).] Hō or dharmas stands for unclearness and unenlightenment [that is, the way we perceive things in our ordinary lives]. So, when unclearness and enlightenment become a single entity, it is called the Utterness of the Dharma (Myōhō). The lotus flower (Renge) stands for the three dharmas of cause, concomitancy and effect. This is the interdependence of cause, concomitancy and effect. Kyō or sutra is the expression of the words, speech, voices, and sounds of all sentient beings. This is explained as when the voice is in the service of the Buddha enlightenment; then this is what is called a sutra. A sutra may also be described as that which is constant and unchanging throughout the past, present, and future. The Dharma realm of the Buddha or all the realms of dharmas of ordinary people are the Utterness of the Dharma (Myōhō, Saddharma). The Dharma realm or the realms of dharmas of ordinary people is the location where they occur (Kyō). The eight-petalled lotus with five Buddhas and four bodhisattvas is the substantiation of the Buddha enlightenment in all of us. You should think this over thoroughly.

The Eight-petalled Lotus with the five Buddhas and the four Bodhisattvas The eight-petalled lotus shows the five Buddhas and the four bodhisattvas [one Buddha in the centre and four others in the cardinal directions], the other four quarter points being occupied by bodhisattvas. This is the same as the mandala of the womb treasury (taizōkai, garbhadātu) that is used by the Tantric and Mantra School (Shingon) in Japan. The womb treasury (taizōkai, garbhadātu) is the fundamental source of enlightenment, as well as life itself. This matrix is comparable to a womb in which a child is conceived. This matrix is comparable to a womb in which a child is conceived. It is both the container and its contents which entails the fundamental of enlightenment and wisdom in its purest state. It also represents the human heart (mind<) in its essential innocence and purity, which is seen as the compassion of the Buddha and his moral awareness. The central Buddha of this mandala is the Tathāgata of the Universal Sun (Dainichi-Nyorai, Mahavairochana-Tāthagata), who emanates his light onto all the other manifestations of wisdom and enlightenment. It is the enlightenment of the original archetypal state (honmon), which induced the teachings of Shākyamuni that were derived from the external events of his life and work (shakumon). On the eastern petal is the Buddha Jeweled Banner (Hōtō, Ratnaketa); on the southern petal sits the Buddha Sovereign of the Flowering of the Whole Surface [to be enlightened] (Kaifuka’ō). On the western petal is the Buddha of Boundless Light (Amitābha Buddha, Amida Butsu), and on the northern petal sits the Buddha who represents the Dharma-kāya or the universal entity of the Buddha (Tenkurai’on, Amoghasiddhi). The remaining petals represent the four bodhisattvas. On the southeastern petal is the Bodhisattva Universally Worthy (Fugen, Samantabhadra); on the northeastern petal sits the Bodhisattva Perceiving the Sounds of the Existential Dimensions (Kanzeon, Avalokiteshvara); on the northwestern petal is the Bodhisattva Maitreya (Miroku); and on the southwestern petal sits the Bodhisattva Mañjushrī (Monjushiri). All these Buddhas and bodhisattvas are seen as the nine honoured ones. Also, the lotus flower in this context is thought of as a symbol for the heart or mind of sentient beings. In the Oral Transmission of the Meaning on the Dharma Flower Sutra (Ongi Kuden), the nine honoured ones are understood as the principle of the nine realms of dharmas not being separate from the Dharma realm of the Buddha. They are the following:

1. The Tathāgata of the Universal Sun (Dainichi-Nyorai, Mahavairochana-Tāthagata)

The transmission goes on to say ther following:

In the First and Introductory Chapter, there are seven important points. All of this comes to a total of two hundred thirty-one items. Apart from these, there is another transmission. All of these have been written down in detail and in full. In the Sutra on Implications Without Bounds (Muryōgi-kyō), there are six important points; and in the Sutra on Practising Meditation on the Bodhisattva Universally Worthy (Fugen, Samantabhadra) [Butsu Setsu Kan Fugen Bosatsu Gyōhō Kyō], there are five important points.

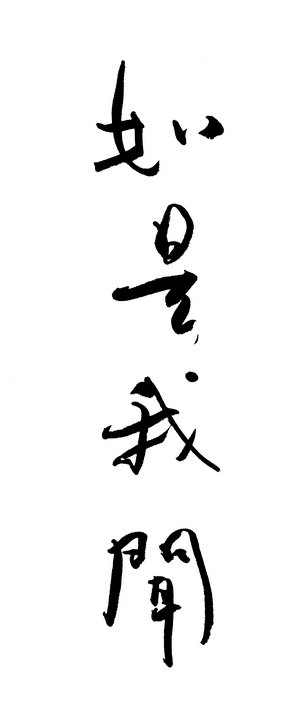

I heard it in this way . . .

The first important point: “I heard it in this way.” It says in the first chapter of the Textual Explanation of the Dharma Flower Sutra (Hokke Mongu): “[The phrase] ‘in this way’ refers to the meaning of the Dharma that was preached by the Buddha. ‘I heard’ implies the person who is able to hold to this Dharma." The Annotations on the Textual Explanation of the Dharma Flower Sutra states, “because the whole Sutra from beginning to end is the content of what the Buddha expounded.” The Oral Transmission on the Meaning of the Dharma Flower Sutra (Ongi Kuden) says that the word “heard” of what was heard implies the second of the six stages of practice, which is the stage when people hear the title Nam Myōhō Renge Kyō and also read the Sutra [i.e., recite gongyō]. They are then able to reason that all existence is endowed with the Buddha nature and are able to open up the Buddha nature within themselves. The meaning of the Dharma is Nam Myōhō Renge Kyō. In regard to being able to hold to the Dharma, one should think very carefully over the word “able” which refers to our personal capabilities. Next, in the first chapter of the Annotations on the Textual Explanation of the Dharma Flower Sutra where it says, “because the whole sutra from beginning to end”, this is made clear by saying that the beginning is “the First and Introductory Chapter”, and the end is the Sutra on Practising Meditation on the Bodhisattva Universally Worthy (Fugen, Samantabhadra) [Butsu Setsu Kan Fugen Bosatsu Gyōhō Kyō]. This is the content of all that was heard. The content of the Dharma is said to be its own essence which is Nam Myōhō Renge Kyō. The Dharma entails all dharmas [i.e., the entirety of existence], and what is said to be the essence of all dharmas is returning our lives to and founding them on the Utterness of the Dharma (Myōhō, Saddharma) permeated by the underlying white lotus flower-like mechanism of the interdependence of cause, concomitancy and effect in its whereabouts of the ten [psychological] realms of dharmas. The Universal Teacher Dengyō (Dengyō Daishi), in order to censure the mistaken views in Ji On’s Esoteric Praise for the Dharma Flower, wrote in his Superiority of the Dharma Flower, “Although somebody may praise the Dharma Flower Sutra (Hokke-kyō), because that person does not know what this sutra is about, he kills its essential meaning.” I must suggest that you should let your mind dwell on the word “kill”. The person with no faith is somebody who is not the hearer who heard the sutra “in this way”. It has to be said that it is the Practitioner of the Dharma Flower Sutra (Hokke-kyō) who has heard its content “in this way”. With regard to this, it says in the first chapter of the Textual Explanation of the Dharma Flower Sutra (Hokke Mongu), [In the phrase] “in this way, ‘this’ implies a faithful compliance, 'faith' means that one has understood the content of what was heard. Compliance means that the teacher leads the disciple to the attainment of the Buddha Path.” Nichiren and his disciples are indeed the people who “heard it this way”.

. . . . at a time when the Buddha was living in Ōshajō (Rājagrha) [the capital of Magadha, present-day Rajgir, Behar] on Spirit Vulture Peak (Ryōjusen, Gridhrakūta), with a large assembly of twelve thousand fully ordained monks. All of them had the supreme reward of the individual vehicle (shōjō, hīnayāna); the vagaries and fantasies in their minds had come to an end; they had no more troublesome worries (bonnō, klesha); and they themselves had attained an independent freedom. Their names were Anyagyōjinnyō (Ajñātakaudinya) . . .

The second important point, concerning Anyagyōjinnyō (Ajñātakaudinya). In the first chapter of the Textual Explanation of the Dharma Flower Sutra (Hokke Mongu), it says: Gyōjinnyo (Kaundinya) is a family name which can be interpreted as “fire vessel”. These people were a family of the Brahmin class. Their ancestors were in the service of worshipping fire. This is the origin of their family name. Fire has two implications – one it gives light and secondly it burns. When fire is giving light, darkness cannot come about, and where there is burning, things cannot come into being. So this person's other name can be understood as “not created” or “non birth”. The Oral Transmission on the Meaning of the Dharma Flower Sutra (Ongi Kuden) says, “The fire is the fire of the wisdom of the Dharma nature and enlightenment." When it comes to the two implications of fire, one is shining, which is the wisdom of the reality as it is according to karrmic circumstances; the other is burning, which is the principle of eternal and unchanging reality. These two words ‘shining’ and ‘burning’ represent the teachings derived from the external events of Shākyamuni’s life and work (shakumon) and also those of the original state (honmon). The ability of fire to burn as well as shine are both the effectiveness of Nam Myōhō Renge Kyō. Nowadays Nichiren and his disciples recite with reverence Nam Myōhō Renge Kyō, so that it shines into and clears away the darkness of living and dying, in order to let the fire of the wisdom of nirvana [i.e., enlightenment] shine brightly. When we realise and understand that the cycles of living and dying are not separate from the oneness of enlightenment it means that enlightenment which entails shining does not let the darkness come about. By burning the firewood of troublesome worries (bonnō, klesha), the fire of the wisdom of enlightenment stands before our eyes. When we also realise and understand that troublesome worries are not separate from enlightenment, then burning means things [such as troublesome worries] cannot come into being. By this, it is suggested that Gyōjinnyo is showing to those of us who are practitioners of the Dharma Flower Sutra (Hokke-kyō) that troublesome worries are not separate from the enlightenment of nirvana.

. . . . Makakashō (Mahākāshyapa), Urobinrakashō (Uruvilvā Kāshyapa), Gayakashō (Gayā Kāshyapa), Nadaikashō (Nadī Kāshyapa), Sharihotsu (Shariputra), Mokuren (Maudgalyāna), Makakasennen (Māhakatyāyana), Anuruda (Aniruddha), Kōhinna (Kapphina), Kyobonhadai, Rihata (Revata), Piryōkabasha, Hakura (Vakkula), Makakuchira, Nanda, Sondarananda, Furuna (Pūrna, Maitrayani-putra) , Shubodai (Subhūti), Anan (Ānanda), as well as Ragora (Rāhula) and other such people, known to the assembly as all having attained the supreme reward of the individual vehicle (shōjō, hīnayāna). Furthermore, there were another two thousand monks who were still learning, in order to get rid of their delusions, as well as others who had gone beyond the need to study. There was the nun Makahajahadai (Mahāprajāpatī), who was accompanied by a suite of six thousand persons. There was the nun Yashudara (Yashōdara) who was the mother of Ragora (Rāhula), also accompanied by her following. There were eighty thousand persons, who were completely evolved bodhiattvas who had refused their own extinction into nirvana for the sake of the Buddha enlightenment of all sentient beings (bosatsu makasatsu, bodhisattva mahāsattva), all of whom had attained the unexcelled, correct, and universal enlightenment (anokutara sanmyaku sanbodai, anuttara samyak sambodhi) and were incapable of giving up their practice. All of them were in possession of incantations that lay hold of the good so that it cannot be lost (dhāranī). They also had a freedom in expounding the truth with the correct meaning and appropriate words. They had set in motion the Dharma Wheel of not turning back and had made offerings to hundreds of thousands of Buddhas. They had all put down good roots of religious power at the places of all the Buddhas, always admiring and praising them. They had sensitized their persons towards compassion and had decidedly entered into the wisdom of the Buddhas, as well as penetrating into the all-embracing comprehension of what existence is all about which includes having arrived at the other shore of nirvana. Their renown had been heard of in innumerable worlds, and they had delivered countless hundreds of thousands of sentient beings to the shores of enlightenment. Their names were the Bodhisattva Mañjushrī (Monjushiri), the Bodhisattva Perceiving the Sound of the Existential Dimensions (Kanzeon, Avalokiteshvara), the Bodhisattva Tokudaisei, the Bodhisattva Jōshōjin, the Bodhisattva Fukusoku, the Bodhisattva Hōshō, the Bodhisattva Sovereign Medicine (Yaku’ ō, Baishajya-raja), the Bodhisattva Yuze, the Bodhisattva Hōgatsu, the Bodhisattva Gakkō, the Bodhisattva Mangatsu, the Bodhisattva Dairiki, the Bodhisattva Muryōriki, the Bodhisattva Otsusangai, the Bodhisattva Baddabara, the Bodhisattva Maitreya (Miroku), the Bodhisattva Hōshaku, and the Bodhisattva Dōshi, as well as other completely evolved bodhiattvas who had refused their own extinction into nirvana for the sake of the Buddha enlightenment of all sentient beings (bosatsu makasatsu, bodhisattva mahāsattva). Then there was Taishaku (Indra) who was King of the deva (ten) [that are shining celestial, godlike beings who protect the Buddha teaching], along with his repective suite of twenty thousand deva princes. Again, their names were the deva Prince Gatten, the deva Prince Fukō, the deva Prince Hōkō, as well as the four deva kings of the four quarters, accompanied by ten thousand deva princes. Then, there were the deva prince Jizai and the deva prince the son of Daijizai, the Great Sovereign, accompanied by their suite of thirty thousand deva princes. Also there was King Bonten (Brahmā), lord of the existential realm that have to be endured (shaba sakai, sahāloka), Shiki Daibon, Kōmyō Daibon, and so forth, with their retinues of twelve thousand deva princes. There were the eight dragon Kings (ryū, nāga) [whose aspect is rather like the dragons in Chinese paintings] – the dragon King Nanda, the dragon King Batsunanda, the dragon King Shakara, the dragon King Washukitsu, the dragon King Tokushaka, the dragon King Anabadatta, the Dragon King Manashi, and the dragon King Uhatsura – each one with a following of several hundreds of thousands. There were the four kings of the kinnara (kimnara) [the musicians of Kuvera the god of riches, they are described as exotic birds with a human torso], the kinnara King Hō, the kinnara King Myōhō, the kinnara King Daihō and the kinnara King Jihō. Each one of these sovereigns was accompanied by a suite of several hundreds of thousands. There were the four kings of the kendabba (gandharva). [These are spirits that live in the Fragrant Mountains and feed on fragrance or incense. They are the musicians of Taishaku and are said to be similar to the kinnara (kimnara).] There was the kendabba King Gaku, the kendabba King Gakuon, the kendabba King Mi, and the kendabba King Mion. Each one of these sovereigns was accompanied by a retinue of several hundreds of thousands. There were the four kings of the shura (ashura). [These beings are often compared to the titans of European mythology. In the Vedic and Brahman mythologies, they are seen as the rivals and enemies of the deva (ten). The Buddha teaching sees them as protectors.] There were the shura King Baji, the shura King Karakendo, the shura King Bimashittara, and the shura King Rago. Each one of these sovereigns was accompanied by a retinue of several hundreds of thousands. There were the four kings of the karura (garuda). [These are a category of non-humans with human intelligence, with wings and the beak of a bird of prey.] There was the karura King Daiitoku, the karura King Daishin, the karura King Daiman, and the karura King Myōi. Each one of these sovereigns was accompanied by a retinue of several hundreds of thousands. Then, there was King Ajase (Ajātashatru) the son of Idaike (Vaidehī) [the wife of Bimbashara (Bimbisāra)], with a following of several hundreds of thousands. All of these persons each one prostrated themselves at the Buddha’s feet, then stepped back to one side, and sat down.

The third important point, concerning King Ajase (Ajātashatru). In the first volume of the Textual Explanation of the Dharma Flower Sutra (Hokke Mongu), it says, “The name Ajase alludes to resentment not yet born.” Again, in the sutra on Shākyamuni’s Final Entrance into the Extinction of Nirvana (Mahāparinirvana Sutra), it says that the name Ajase means “a resentment not yet born.” Again, in this sutra, it states that, “Aja" means ‘unborn’, and the ideogram for world ‘se’ denotes resentment or hatefulness. It says in The Oral Transmission on the Meaning of the Dharma Flower Sutra (Ongi Kuden): All the sentient beings of Japan are just like King Ajase (Ajātashatru), on account of their slander. They have already killed all the Buddhas, their father, and have brought about harm to their mother, the Dharma Flower Sutra (Hokke-kyō). In the Sutra on the Implications Without Bounds (Muryōgi-kyō, Āmitārtha-sūtra), “The King of all the Buddhas and the Queen who is the Dharma Flower Sutra (Hokke-kyō) come together and jointly parent this bodhisattva son.” Those people who slander the Dharma even while they are still in their mother’s womb are already bearing resentful hatred towards the Dharma Flower Sutra (Hokke-kyō). So are these people the enemy who has not yet been born? Furthermore, at the present time in Japan, there are three kinds of powerful enemy. The ideogram for world “se” entails the meaning of hatefulness. It suggests that we should pay attention to this last phrase. But those who are the followers of Nichiren can avoid the consequences of this heavy wrongdoing. Even though we are people who have slandered the Dharma, by having faith in the Dharma Flower Sutra (Hokke-kyō) and by taking refuge in the Eternal Shākyamuni who lies within the text, how can we not blot out the former heavy sin of killing our fathers [all the Buddhas] and killing our mothers [the Dharma Flower Sutra (Hokke-kyō)]? However, even though they are our father and mother, but since they have no faith in the Dharma Flower Sutra (Hokke-kyō) should we not just kill them – the reason being that, if our love for the temporary doctrines becomes our archetypal mother and if we have an archetypal father who is incapable of distinguishing between the teachings that are an expedient means and those that are the truth, then should we not kill them both? According to the Textual Explanation of the Dharma Flower Sutra (Hokke Mongu), it says, “When we think things over and apply reason then doing harm to an archetypal mother who is greedy and possessive or to an archetypal father who is unenlightened is contrary to our moral values. But this reversal in behaviour becomes a compliance with moral conduct, when we do something contrary to custom so that we can penetrate further into the Buddha path.” Thinking things over and applying reason in this present age that is the final period of the Buddha teaching of Shākyamuni (mappō), then thinking things over and applying reason must be to chant the theme and title (daimoku). When offspring do harm or kill their father and mother, it is a crime contrary to our values. But when we kill the archetypal father and mother who are both the embodiment of no faith in the Dharma Flower Sutra (Hokke-kyō), then this becomes an act of moral righteousness. Here in this commentary, it is explained as a crime contrary to our values that becomes an act of ethical virtue. In this sense, Nichiren and those that follow him are comparable to King Ajase, since they take up the sword of Nam Myōhō Renge Kyō to kill the archetypal mother who is greed and selfishness and the archetypal father who is unenlightenment. Yet, in the same way as the Eternal Shākyamuni Lord of the teaching, they strive to feel the attainment of total enlightenment. In the Thirteenth Chapter on Exhorting the Disciples to Hold to the Buddha Teaching of the Dharma Flower Sutra (Hokke-kyō), it says, "With regard to the three powerful enemies, the archetypal mother who is greed and selfishness refers to the ordinary people who attack those who dedicate themselves to the Dharma Flower Sutra (Hokke-kyō). The archetypal father who is unenlightened stands for the second and third enemies, who are monks and the Buddhist clergy.”

Then the World Honoured One was surrounded by monks and nuns, along with male and female devotees, who made offerings and rendered homage as well as doing honour and giving praise. The Buddha expounded the sutra of the universal vehicle, called the Sutra on the Implications Without Bounds (Muryōgi-kyō, Āmitārtha-sūtra), which is a Dharma for the instruction of Bodhisattvas and borne in mind by the Buddhas.

The fourth important point: “what is borne in mind by the Buddhas”. In the third volume of the Textual Explanation of the Dharma Flower Sutra (Hokke Mongu), it says, “What is borne in the mind by the Buddhas is the basis that has incalculable implications, and it is the focal point from which they attained the truth by personal experience. It is for this reason that the Tathāgata bears this point in mind.” Later on, in the Second Chapter on Expedient Means, it says, “The Buddha himself abides in the universal vehicle (daijō, mahāyāna).” Even though he wished to reveal and make this essential point known, because the propensities of sentient beings were dull, the Buddha remained silent about this essential point and did not hastily and recklessly expound its meaning. This is why he bore it in mind. In the third volume of the Collection of Notes on the Textual Explanation of the Dharma Flower Sutra, it says, “In the past he had not expounded it. Therefore, this implies that he vigilantly kept it back. With regard to the Dharma and with people’s propensities, it was all held back and borne in mind. . . . . . Because people’s propensities had not yet sufficiently evolved he hid it without expounding it; therefore, he bore it in mind. . . . . .Because he had not yet expounded it means he held it back. By not yet having told the world about it means that it was present in his mind. When it says he remained silent about it for a long time it means a long time ago [i.e., since Shākyamuni started preaching, up to the present moment described in the Dharma Flower Sutra (Hokke-kyō)]. As to what this essential point means, you should ponder it over and over and get to know its implications [see the Sixteenth Chapter on the Lifespan of the Tathāgata]. In The Oral Transmission on the Meaning of the Dharma Flower Sutra (Ongi Kuden), Nichiren states, “The substance was of what was held back and borne in mind by the Buddha was the five ideograms for the title of both the teachings derived from the external events of Shākyamuni’s life and work (shakumon) and from those of the original state (honmon) Myō – Hō – Ren – Ge – Kyō.” What Shākyamuni bore in mind was pondered over in seven different ways. The first was from the viewpoint of time; the second was from the viewpoint of people’s propensities; the third was from the viewpoint of the persons to whom he was trying to communicate this point; the fourth was from the viewpoint of the teachings derived from the external events of Shākyamuni’s life and work (shakumon) and from those of the original state (honmon); the fifth was from the viewpoint as to how it would apply to our minds and bodies; the sixth was from the viewpoint of the embodiment of this Dharma; and the seventh was from the viewpoint of a mind of faith. Now Nichiren and his followers are propagating this embodiment of the Dharma [i.e., its Universal Esoteric Dharma] that had been held back and borne in mind by the Buddha. First from the viewpoint of time; Shākyamuni held back and bore in mind the Dharma Flower Sutra (Hokke-kyō) for more that forty years, because the right time had not yet come about. Secondly from the viewpoint of people's propensities, “Because they cheapen and impair the values of the Dharma and refuse to hold faith in it, they will fall into the three evil dimensions of the suffering of the hells, the craving and wanting of the hungry ghosts, or the stultifying, instinctive taint of animality.” This is why Shākyamuni did not expound this Dharma for forty years. Thirdly, with regard to the person to whom the Buddha intended to expound this Sutra, it was to be Sharihotsu (Shariputra). But Shākyamuni had to wait until Sharihotsu (Shariputra) was ready (shakumon) for the teachings of the original state (honmon). Fourthly, the expressions “to keep” or “to bear” were ascribed to the teachings of the original state (honmon), whereas “at present in mind” is attributable to the teachings derived from the external events of Shākyamuni’s life and work (shakumon). Fifthly, in connection with our minds and bodies, “to keep” is something physical, so it concerns our bodies. What was present in the Buddha’s mind refers to his mind only. Fifthly we come to the embodiment of this Dharma, which is that which exists inherently and has continued eternally. This is the inherent Buddha mind of pity and compassion for all sentient beings. Seventhly, with regard to a mind of faith, then a mind of faith should be fundamentally kept present in our minds. As a result Nichiren and his followers, by reverently reciting Nam Myōhō Renge Kyō, are nevertheless opening up in essence what was kept and borne in mind. “Keeping” is the Buddha’s vision and insight. What is present in the Buddha’s mind is the penetrative power of his wisdom. The two ideograms for penetrative wisdom (chi) and vision and insight (ken) correspond to the two gateways to the Dharma – both the teachings derived from the external events of Shākyamuni’s life and work (shakumon) and that of the original state (honmon). The penetrative power of the wisdom of the Buddha is Utterness (myō), and the vision and insight, of the Buddha is the Dharma (hō). The substance of practising the penetrative power of this wisdom, along with this vision and insight is called the lotus flower (renge) which is the substance of the interdependence of cause, concomitancy and effect. When this interdependence of cause, concomitancy and effect is expressed in words, it becomes the sutra (kyō). At the same time, those who do the practice of the Dharma Flower Sutra (Hokke-kyō) will be borne in mind. In The Twenty-eighth Chapter on the Persuasiveness of the Bodhisattva Universally Worthy (Fugen, Samantabhadra), it says, “First they will be borne in mind by all the Buddhas.” ‘Bearing in mind’ means bearing Nam Myōhō Renge Kyō in our minds. When all the Buddhas bear in mind those who do the practice of the Dharma Flower Sutra (Hokke-kyō), they are keeping present in their minds Nam Myōhō Renge Kyō. The propensities of those of us who recite the title and theme (daimoku) become a oneness with the objectivity of the Fundamental Object of Veneration (gohonzon),as well as our subjective attitudes towards it. Hence, all the Buddhas of the past, present and future keep it present in their minds This is what is meant in the third volume of Myōraku’s (Miao-lo) Collection of Notes on the Textual Explanation of the Dharma Flower Sutra, where he says, “With regard to the Dharma and people's propensities, it was all borne in mind.” In the third volume of the Textual Explanation of the Dharma Flower Sutra (Hokke Mongu), it emphasizes this point, by saying, “The earlier augury of the earth quaking was enhanced by the words ‘bearing in mind’. The shaking of the earth symbolises the Buddha having broken through six stages of the barriers of delusion. The person who accepts and holds to the Sutra on the Lotus Flower-like Mechanism of the Utterness of the Dharma (Myōhō Renge Kyō) or Nam Myōhō Renge Kyō will, without doubt, break through all the six stages of the barriers of delusion.” In the Twenty-First Chapter on the Reaches of the Mind of the Tathāgata, we have this statement, “After I have passed over to the extinction of nirvana, you must accept and hold to this Sutra. Such a person who does so will, without doubt, be decidedly set upon the Buddha path.” This is what is meant by “The Buddha himself abides in this universal vehicle (daijō, mahāyāna).” Again, in another way of thinking, with regard to the Buddha bearing all sentient beings in mind, is that the word “bear” or “keep safe” or “protect” (mamoru) is as in the sentence, “I am the only person who can save and keep other people safe.” The ideogram for “at present in mind” is as in the following sutric sentence, “I continually keep this thought present in my mind” (mai ji sa ze nen) which is in the Sixteenth Chapter on the Lifespan of the Tathāgata. So when we come to theTwenty-eighth Chapter on the Persuasiveness of the Bodhisattva Universally Worthy (Fugen, Samantabhadra), we have the same idea in the sentence, “First they will be borne in mind by all the Buddhas.” Ever since Nichiren was thirty-two years old, he has kept in mind Nam Myōhō Renge Kyō.

. . . . After the Buddha had finished expounding this Sutra, he sat down with his legs crossed with the soles of his feet turned upwards. He then entered the samādhi, that is to say, he went into a meditative state of perfect absorption into the Sutra on the Implications Without Bounds (Muryōgi-kyō, Āmitārtha-sūtra). His mind and body became motionless. At that moment the heavens rained coral tree flowers, giant coral tree flowers, manjusaka flowers, and giant manjusaka flowers which scattered over the Buddha, the monks, nuns, and the lay devotees, both male and female. Throughout all the existential dimensions where there was a Buddha presence, the six kinds of earth tremor quaked – the east rose and the west sank; the west rose, the east sank; the north rose, the south sank; the south rose and the north sank; the middle ground rose the borders sank; the borders rose and the middle ground sank. Thereupon the monks, nuns, along with the devotees of both sexes as well as the non-humans with human intelligence in the assembly, such as the deva (ten), dragons (ryū, nāga), yasha (yaksha) who were earth spirits and guardians of the Dharma, the kendabba (gandharva), shura (ashura) [who are like the titans in Greek mythology], karura (garuda), kinnara (kimnara) and the magoraga (mahorāga) [that are serpents that slither on their chests], as well as all the lesser sovereigns and sage-like rulers whose chariots roll everywhere (tenrinō), were all taken aback at this presage without precedent. Joyfully they put their ten fingers and palms together in obeisance and, with a oneness of mind, looked upon the Buddha with reverence. Then, at the same time, the white curl between the Buddha’s eyebrows let out a light that lit up eighteen thousand worlds in the eastern direction. There was no place whereupon it did not shine. It shone down as far as the Hell of Incessant Suffering, the last and deepest of the eight hot hells, where the sufferers writhe in pain, die, and are instantly reborn to agony.

The fifth important point; the light shone downwards as far as the Hell of Incessant Suffering. This testimony goes to show that all the sentient beings of the ten [psychological] realms of dharmas can become fully enlightened [attain Buddhahood]. It is in the chapter following the Chapter on Seeing the Vision of the Stupa made of Precious Materials that is to say, the Chapter on Daibadatta (Devadatta), where his attainment to Buddhahood [enlightenment] is expounded. This is the chapter in which the Buddha argued forcibly how Daibadatta (Devadatta) and the Dragon King’s daughter (Ryūnyo, Nāgakanyā) became enlightened. At the time of this particular passage in the Dharma Flower Sutra (Hokke-kyō), Daibadatta (Devadatta) had already become enlightened [attained Buddhahood]. The ideogram for “as far as” refers to where the light went, from the curl of white hair between the Buddha’s eyebrows. The light from this curl of white hair is Nam Myōhō Renge Kyō. “Upwards as far as the Akanita Heaven” in the Brahmanistic system is the highest of the eighteen heavens of the world of materiality. Beyond this heaven, there only exists consciousness without form. This heaven is the relativity (kū) of or what is in the mind. Downwards as far as the Hell of Incessant Suffering refers to the self-evident truth of phenomenon “ke” or materiality. The light from the white curl between the Buddha’s eyebrows is the middle way of reality. This is neither simply what is in our minds nor the various phenomena which confront us all, but an inclusion of the two which form the different realities we all experience. According to this, it becomes apparent that the ten realms of dharmas of our subjective lives open up our inherent Buddha nature. In the Twelfth Chapter on Daibadatta (Devadatta), it says that, when this personage attains Buddhahood or enlightenment, he will have the distinction of having the title, “the Buddha who is the Celestial Sovereign (Tennō Butsu)”. At this point, if we think about our respective environments and our subjective lives opening up their inherent Buddha natures or, in other words, becoming Buddhas, then, when the text of this Introductory Chapter mentions, “down as far as the Hell of Incessant Suffering”, it implies that all the objectivity that surrounds us in our lives opens up its inherent Buddha nature. However, when in the Chapter on Daibadatta (Devadatta) it is pointed out that Daibadatta (Devadatta) will be called Celestial Sovereign Tathāgata [i.e., he who has arrived at true reality], it means that the subjective life of Daibadatta (Devadatta) has opened up its inherent Buddha nature. What is being said is that, due to the practice of the Utterness of the Dharma (Myōhō, Saddharma), both our subjective lives (shōhō) and their dependent objectivity (ehō) open up their inherent Buddha nature [or become Buddhas]. Nowadays when Nichiren and his followers pay their respects to the dead, they recite and read (dokuju) the Dharma Flower Sutra (Hokke-kyō) and reverently recite Nam Myōhō Renge Kyō. The light from the title and theme (daimoku) reaches as far as the Hell of Incessant Suffering, so that the deceased can become aware of their own inherent Buddha nature with their persons just as they are. The rites for devoting our merits for the salvation of others as well as the dead have their origin in this concept. Even though people who have no faith in the Dharma Flower Sutra (Hokke-kyō) may fall into the Hell of Incessant Suffering, as compassionate people who do the practices of the Dharma Flower are able to offer sympathy through the ray of light of the title and theme (daimoku), then how could the meaning of this concept be any different for those who have faith in this teaching? Accordingly, Nichiren takes it as given that the passage “downwards as far as the Hell of Incessant Suffering” means that the Buddha let forth a ray of light, so that Daibadatta (Devadatta) could open up his inherent Buddhahood.

. . . . and upwards as far as the Akanita heaven. In this world all the beings of the six paths of sentient existence [i.e.,, 1) those who dwell in the various hells, jigokukai, 2) hungry and famished beings who are always wanting, gakikai, 3) animality which includes animalistic or instinctive behaviour, chikushōkai, 4) the shura (ashura) or power complex and angry behaviour, shurakai, 5) normal human equanimity, ninkai, 6) deva or temporary joy or happiness, tenkai] of that terrain everywhere, along with all the Buddhas present in it were made visible. Likewise, one could listen to all the Dharmas of the Sutras that were being expounded and also all the monks, nuns, male and female devotees, as well as all their practices in order to attain to the Path. In addition, the various causes and karmic circumstances of the fully evolved bodhisattvas who have refused their own extinction into nirvana for the sake of the Buddha enlightenment of all sentient beings (bosatsu makasatsu, bodhisattva mahasattva), with their differing levels of faith and understanding, and also the way they appear, were perceptible as well. Besides one could observe the extinction of all mental and physical activity of the passing over to nirvana of all the Buddhas. And also, after their passing over to nirvana, one could gaze upon all the stupas made of the seven precious materials that were to serve as reliquaries for them. Then this thought came into the Bodhisattva Maitreya’s (Miroku) mind: “At present, the World Honoured One is manifesting these illusions that are causing changes in the natural order of events. What are the causes and karmic circumstances these premonitory signs are going to bring about? Just now, the World Honoured One has gone into the deep absorption of the one object of meditation (sanmai, samādhi). Whom should I ask about this inexplicable, extraordinary apparition, and who could give me a real answer?" Again, Maitreya (Miroku) thought to himself, “There is Mañjushrī (Monjushiri), this prince among the kings of the Dharma who has already in the past approached and made offerings to innumerable Buddhas. He must surely have seen this astonishing event. I really should ask him now.” Just then the thought occurred to all of the monks, nuns and lay devotees of both sexes, as well as all the deva (ten), dragons (ryū, nāga), disembodied spirits and lesser divinities, as to whom they should inquire about the bright, shining light and also all this phenomena brought about by the reaches of the Buddha’s mind. Thereupon the Bodhisattva Maitreya (Miroku), desirous to settle his own doubts, as well as being aware of those of the assembly of monks, nuns, male and female devotees together with all the deva (ten), dragons (ryū, nāga), disembodied spirits and divinities, questioned Mañjushrī (Monjushiri), in this manner: What causes and karmic circumstances bring about these presages and these phenomena, which are the reaches of the mind of the Tathāgata – the unleashing of this great light that shines into eighteen thousand distant dimensions, all of them revealing their Buddha abodes, their boundaries, and their respective ornamentations? Again, the Bodhisattva Maitreya (Miroku) wished to reiterate this question of why is it that our guide and teacher emits light from the curl between his eyebrows . . .

The sixth important point: “Why is it that our guide and teacher . . . .” In the third volume of the Textual Explanation of the Dharma Flower Sutra (Hokke Mongu), it says, “Indeed, if you think about it, a person who can expound the Dharma and then enter into a perfect absorption into a single object of meditation and is able to guide people has already been pointed out as a guide and teacher.” The Oral Transmission on the Meaning of the Dharma Flower Sutra (Ongi Kuden) states that this “guide and teacher” refers to the Shākyamuni Buddha of the original state. The Dharma that was preached was the Sutra on Implications Without Bounds (Muryōgi-kyō). The perfect absorption into the one object of meditation was the perfect absorption into the incalculable implications of Nam Myōhō Renge Kyō. As things may turn out, there are two kinds of ‘guide and teacher’ – bad guides and teachers and good guides and teachers. The bad guides and teachers are Hōnen of the Pure Land School (Jōdo), Kōbō of the Esoteric School (Shingon), and Jikaku and Chishō who were the turncoats of the Tendai School. The good guides and teachers are those like Tendai (T’ien T’ai) and Dengyō (Dengyō Daishi). Now that we have entered the final period of the teaching of Shākyamuni (mappō), Nichiren and those that follow him are good guides and teachers. The Dharma that they explain is Nam Myōhō Renge Kyō, and their absorption into a single concept consists of a firmly fixed mind to receive and hold to the Dharma Flower Sutra (Hokke-kyō). With regard to the phrase “able to guide people”, you should bear in mind the word able and ponder over its implications. In our school, the word able has an undertone of being enlightened, as in the case of the Buddha being able to guide and teach. In the Chapter on the Bodhisattvas who Swarm up out of the Earth, the expression “guide and teacher of the chant” has the same meaning as the “guide and teacher” in the First and Introductory Chapter of the Dharma Flower Sutra (Hokke-kyō). Accordingly, it refers to the person who will lead all sentient beings of the World of Humankind (Nihonkoku), by expounding the Dharma to them.

The Bodhisattva Maitreya (Miroku) then recited this question in the form of the following metric hymn: He also makes it rain coral tree

Then Mañjushrī (Monjushiri) answered, by addressing Maitreya (Miroku) the completely evolved bodhisattva who had refused his own extinction into nirvana for the sake of the Buddha enlightenment of all sentient beings, as well as all persons of learning: All you good people, what I think is going to happen is that now the World Honoured One is about to expound the all-embracing Dharma. He is going to make the rain of this all-embracing Dharma come streaming down. He is going to blow the conch shell of the universal Dharma, since it is his desire to preach its meaning. All you good people, in a past I have already seen these auspicious omens, in the presence of all the Buddhas, who after emitting this light thereupon preached the universal Dharma. Therefore, you should know that it is just like those other occasions. Now that the Buddha has manifested this light, and since he is a sentient being, he wishes that all the existential spaces everywhere will get to hear and know about this Dharma that is difficult to have faith in – hence the appearance of these signs. All you good people, in a past of boundlessly inconceivable myriads of myriads of myriads of kalpas, there was at that time a Buddha who was called the Tathāgata [i.e., he who had arrived at true reality] of the Brightness of the Light of the Sun and Moon and who had the ten titles of Tathāgata – 1) One who has arrived at a perfect understanding of the suchness of existence (Nyorai, Tathāgata); 2) Worthy of offerings (Ōgu, Arhat); 3) Correctly and universally enlightened (Shōhenchi, Samyak Sambuddha); 4) Whose knowledge and conduct are perfect (Myōgyō-soku, Vidyā-charana-samppanna); 5) Who is completely free from the cycles of living and dying (Zensei, Sugata); 6) Understanding of the realms of existence (Sekenge, Lokavit); 7) Supreme Lord (Mujōji, Anuttara); 8) The Master who brings the passions and delusions of sentient beings into harmonious control (Jyōgo-jōbu Purusha-damaya-sārathi); 9) The Teacher of humankind and the deva (ten) (Tenninshi, Shasta-deva-manushyanam); 10) and the Buddha who is the World Honoured One (Seson, Bhagavat). This Buddha expounded the correct Dharma, of which the prelude was good, the middle part was good, and the end part was good. The meaning of this Dharma was profound and broad. It was taught with skilfulness. By being pure and free from admixtures this Dharma was fully endowed with the pure whiteness of the practice of the Brahmans. For those who were seeking to become hearers of the voice (shōmon, shrāvaka), who exerted themselves to attain the highest stage of the individual vehicle (shōjō, hīnayāna) through listening to the discourses of the Buddha and today would be seen as intellectual seekers. This Tathāgata taught the Dharma according to the four and primary doctrines of the Buddha teaching, which imply existence is suffering, human passion is the cause of continued suffering, that by elimination of human passions existence may be brought to an end, and that by a life of righteousness the destruction of human passions may be attained. Such a teaching would carry these people through living, maturing and growing old, sickness, and dying, and ultimately bring about nirvana, which is the total extinction of being. For those who sought enlightenment for themselves (engaku, hyakushibutsu, pratyekabuddha), this Buddha expounded a teaching adapted to the twelve causes and karmic circumstances that run through sentient existence. [These are 1) a fundamental unenlightenment which leads to the 2) natural tendencies and inclinations that are inherited from former lives, 3) the first consciousness after conception that takes place in the womb, 4) body and mind evolving in the womb, 5) the five organs of sense and the functioning of the mind, 6) contact with the outside world, 7) receptivity or budding intelligence and discrimination from six to seven years onwards, 8) desire for amorous love at the age of puberty, and 9) the urge for a sensuous existence that forms 10) the substance of future karma, 11) the completed karma ready to be born again, 12) which faces in the direction of future old ages and deaths.] For those people who, due to practice over a number of years, have become altruists that strive to save humanity from itself through the Buddha teaching, as well as being for universal enlightenment – that is to say, bodhisattvas (bosatsu) who practise and study for the benefit of others as well as for themselves – this Tathāgata expounded a teaching based on six main items that ferry people across the sea of living and dying to nirvana as the complete extinction of being (ropparamitsu, the six paramitas). These six are by charity and giving, by keeping to the Buddhist precepts, patience under insult, zeal and progress, meditation or contemplation, wisdom, the power to discern the truth, which is the real aspect of all dharmas, and to be able to attain the highest, correct, and complete wisdom of Buddhahood (anokutara sanmyaku sanbodai, anuttara-samyak-sambodhi), which is also the sum total of wisdom in all its aspects. Then there was another Buddha who was also called the Brightness of the Light of the Sun and the Moon. Then, in the same way, there were another twenty thousand Buddhas all with the same personal name, the Brightness of the Light of the Sun and Moon, and who had the same family name, Harada. Maitreya (Miroku), you ought to know that, from the first to the last Buddha, all had the same personal name, the Brightness of the Light of the Sun and Moon, and they were all in possession of the ten titles of the Buddhas. [These were Tathāgata (he who comes to the suchness of reality), Worthy of Offerings, Correctly and Universally Enlightened, Whose Knowledge and Conduct is Perfect, Completely Free from the Cycles of Living and Dying, A Complete Understanding of the Realms of Existence, Supreme Lord, The Master who brings the Passions and Delusions under Harmonious Control, Teacher of the Deva and Humankind, The Buddha who is the World Honoured One.] Also the Dharma that they taught was good at the beginning, good in the middle, and good at the end. Before the very last of these Buddhas had left his family in order to become an ascetic, he had eight sons who were princes. The first prince was called Gifted with Purpose; the second prince was called Purpose of Good; the third prince was called Boundless Purpose; the fourth prince was called Purpose Without Price; the fifth prince was called Intensified Purpose; the sixth prince was called Purpose without Doubt; the seventh prince was called Resounding Purpose, and the eighth prince was called Purpose of the Dharma. Each one of these princes ruled in sovereign majesty over a world with four continents (Shitenkai). When these princes heard that their father had left his family to become an ascetic and had attained the unexcelled, correct, and universal enlightenment (anokutara sanmyaku sanbodai, anuttara-samyak-sambodhi), all of these princes renounced their royal thrones and left their families, so as to become ascetics. They revealed the meaning of the universal vehicle (daijō, mahāyāna), constantly practising the discipline of pure living, which ensures rebirth in the heavenly realms beyond form (bongyō) as well, as becoming teachers of the Dharma. Meanwhile, they all put down roots of goodness, in the presence of thousands of myriads of Buddhas. At this time, the Buddha of the Brightness of the Light of the Sun and Moon expounded the sutra of the universal vehicle (daijō, mahāyāna), entitled the Sutra on the Implications Without Bounds (Muryōgi-kyō, Āmitārtha-sūtra), which was a teaching for the instruction of bodhisattvas that was borne in mind by the Buddhas. When he had finished preaching this sutra he sat down with his legs crossed, in the middle of the assembly. Then, he entered into a state of perfect absorption into the mental space where the Sutra on the Implications Without Bounds (Muryōgi-kyō, Āmitārtha-sūtra) is to be found. Both his body and mind became motionless. At that moment, the heavens rained down coral tree flowers, big coral tree flowers, manjusha flowers, and large manjusha flowers which were strewn over the Buddha and the great assembly. Everywhere in the existential dimensions of the Buddhas, the earth quaked in six different ways – the east rose and the west sank; the west rose and the east sank; the north rose and the south sank; the south rose and the north sank; the middle ground rose and the borders sank; the borders rose and the middle ground sank. Thereupon all the monks, nuns, along with both the male and female devotees in the assembly, as well as the deva (ten) who are shining celestial godlike beings who protect the Buddha teaching, dragons (ryū, nāga) [whose aspect is like those in Chinese paintings], the yasha (yaksha) [that are nature spirits similar to gnomes], the kendabba (gandharva) [that are spirits who live in the Fragrant Mountains and feed on fragrance], the shura (ashura) [who are the titanic rivals of the deva (ten)], the karura (garuda) [that have wings and the beaks of birds of prey], the kinnara (kimnara) [that are exotic birds with human torsos], and the magoraka (mahorāga) [that are serpents who crawl on their chests], as well as the minor sovereigns and the sage-like sovereigns whose chariot wheels roll everywhere without hindrance (tenrinnō, chakravartin) – all of this huge assembly was taken aback at this event that had apparently never happened before. Joyfully they put the palms of their hands together and, with the whole of their minds gazed in the direction of the Buddha. Then, at that moment, this Tathāgata sent out a light from the curl between his eyebrows that shone in the direction of the east, lighting up eighteen thousand existential realms of Buddhahood, so that there was nowhere that was not bathed in splendor, in the same way as all the Buddha terrains had been illuminated just now. Maitreya (Miroku), indeed you should know that, at that time, in the assembly there were twenty myriads of bodhisattvas who joyfully wished to listen to the Dharma. When these bodhisattvas saw how the light shone onto all the Buddha terrains everywhere they were taken by surprise and wanted to know what the cause and karmic circumstances for this radiance was. Then there was a bodhisattva called Myōkō, the Utterness of Light, who had eight hundred disciples. At that moment, the Buddha of the Brightness of the Light of the Sun and Moon came out of his meditation and, on account of the Bodhisattva Utterness of Light (Myōkō), expounded the sutra of the universal vehicle (daijō, mahāyāna) called the Sutra on the Lotus Flower of the Utterness of the Dharma (Myōhō, Saddharma), a teaching for the instruction of bodhisattvas which is borne in mind by the Buddhas. For a period of sixty intermediate kalpas, this Tathāgata did not get up from his seat, and those who were attending at that time in the assembly also remained seated in their places for the duration of sixty intermediate kalpas without moving their bodies or their minds wavering. It is said that for those who were listening to that Buddha’s discourse, it seemed like the lapse of time for a meal. During all that time, there was not a single person in that assembly whose body became listless or whose mind lost interest. When the Buddha of the Brightness of the Light of the Sun and Moon had, after sixty intermediate kalpas, finished expounding this sutra, he then stated the following words to Bonten (Brahmā) and the Demon King of the sixth and highest of the Brahmanic heavens where there are desires and who also wastes away the efforts and accomplishments of other people for his own pleasure (Dai Roku Ten no Ma' ō), as well as to the religious novices, deva (ten), humankind, and shura (ashura), who were in the assembly: “Tonight, at midnight, I will enter the total extinction of nirvana." At that time, there was a bodhisattva who was called Store of Virtue (Tokuzō). The Buddha of the Brightness of the Light of the Sun and Moon thereupon foretold this disciple's future attainment to Buddhahood, including his respective Buddha kalpa, Buddha realm, and his various titles. Then, he said to the monks, “This Bodhisattva Store of Virtue (Tokuzō) will in time come to realise the harvest of enlightenment. His name will be the Tathāgata Pure Person (Jōshin) who has accomplished the supreme reward of the individual vehicle (shōjō, hīnayāna), as well as being completely and perfectly enlightened.” Having foretold the future Buddhahood of the Bodhisattva Store of Virtue (Tokuzō), this Buddha then entered the complete extinction of nirvana that has no residue, at midnight. After the Buddha of the Brightness of the Light of the Sun and Moon had passed over to the total extinction of nirvana, the Bodhisattva Utterness of Light (Myōkō), who had held to the teaching of the Sutra on the Lotus Flower of the Utterness of the Dharma (Myōhō Renge Kyō), spent a full eighty intermediate kalpas in expounding it to humankind. As for the eight sons of the Buddha of the Brightness of the Light of the Sun and Moon, they all accepted Utterness of Light (Myōkō) as their teacher, whose emancipating instruction confirmed and consolidated their realisation of the unexcelled, correct, and universal enlightenment (anokutara sanmyaku sanbodai, anuttara-samyak-sambodhi). These princes after having made offerings to hundreds of thousands of tens of thousands of myriads of Buddhas, all of them attained to the path of Buddhahood. The very last person to become a Buddha was called Burning Lamp (Nentō), and among his eight hundred disciples there was a person called Seeker of Renown (Gumyō), who was greedy and attached to money and eating. Even though he recited and read all the sutras, he was unable to let them sink in or have any advantage from them; also, he forgot a number of passages from these texts. This is why he was called Seeker of Renown (Gumyō). He had, nevertheless, the causes and karmic circumstances of having put down the good roots of being able to encounter, make offerings, render homage, and show great reverence and praise to countless hundreds of thousands of tens of thousands of myriads of Buddhas. Maitreya (Miroku), you ought to know that the Bodhisattva Utterness of Light (Myōkō) of that time could have been no one else but myself (Mañjushrī, Monjushiri), and the Bodhisattva Seeker of Renown (Gumyō) was you in person. Now these auspicious signs that we were gazing at are not different from those of other times. This is why, according to my judgment, the Tathāgata is in fact going to preach the sutra of the universal vehicle (daijō, mahāyāna) that is called the Sutra on the White Lotus Flower-like Mechanism of the Utterness of the Dharma (Myōhō Renge Kyō), which is for the instruction of bodhisattvas and is borne in mind by the Buddhas. Thereupon Mañjushrī (Monjushiri), in the midst of the assembly, wishing to reiterate this idea, expressed it in the following metric hymn: I remember in an age

The seventh important point: “the drums of the deva (ten) rumbled on their own”. In the third volume of the Textual Explanation of the Dharma Flower Sutra (Hokke Mongu), it says that the drums of the deva (ten) rumbling on their own expresses the concept of the Buddha preaching, without the preliminary formalities of being asked to. In the Oral Transmission on the Meaning of the Dharma Flower Sutra, the metric hymn that includes the phrase, “The drums of the deva (ten) rumbled on their own”, is a lengthy praise of how the omens in this existential dimension of ours and the omens in all the other dimensions are exactly the same. The expression “preaching without being asked to” refers to the Tathāgata Shākyamuni expounding the Sutra on the Lotus Flower-like Mechanism of the Utterness of the Dharma (Myōhō Renge Kyō), without anybody asking him to do so. Now Nichiren and those that follow his teachings declare without anyone asking them that the taking refuge in and reciting the name of the Buddha Amida (Amitābha) (Nenbutsu) leads to the Hell of Incessant Suffering, the practices of the Zen School are the invocation of the Demon King of the sixth Brahmanic heaven where desires and forms still exist (Dai Roku Ten no Ma' ō), the Tantric School (Shingon) leads to the ruin of the nation and the school that bases its teaching on the strict observance of the monastic rules (Risshu) is the robber of the state. Because all three teachings are provisional and incomplete, they cannot lead to enlightenment. So yelling such things out becomes preaching without being asked to do so. This incurs the presence of the three kinds of powerful enemy, who are 1) ordinary people that do not understand the Buddha teaching, who vilify and make fun of those who do the practices of the Dharma Flower, as well as attacking them with swords and staves, 2) arrogant monks who think they have attained enlightenment and therefore slander the people who practise sincerely, and 3) monks in high places as well as being respected by the credulous, who for fear of losing their reputations and gain, incite people to persecute those who dedicate their lives to the teachings of Nichiren. The drums of the deva (ten) are Nam Myōhō Renge Kyō. “On their own” is that Nam Myōhō Renge Kyō entails the whole of the workings of existence, so that no obstacle can stand in its way. “The rumbling of the drums” is the sound of reciting the title and theme (daimoku). Another implication of the word rumbling is that all sentient beings are freely giving vent to their speech, words, sounds, and voices that become an analogy of preaching without being asked to. “Preaching without being asked to” also has the nuance of the cries of sinners being chastised by the lictors of hell, as well as the craving and wanting of the addict-like hungry ghosts, or even the vibrations of the continual chain of things that occur in the minds of all sentient beings when they are set upon by the three poisons of greed, anger, and stupidity. The reality of these sounds and voices is the whereabouts of the simultaneousness of the causes and effects throughout the whole of existence, which is Myōhō Renge Kyō. The drums of the deva (ten) are the five ideograms for the Sutra on the Lotus Flower of the Utterness of the Dharma (Myōhō Renge Kyō) which includes both the teachings derived from the recorded external events of Shākyamuni’s life and work (shakumon), as well as those that refer to the original state (honmon). “The deva”, whose abode is in the heavens, points to the uppermost reality which is enlightenment. “Preaching without being asked to” entails the explanation of the Dharma that is received from and used by, as well as enjoyed by, the Buddha himself. In volume three of Myōraku’s (Miao-lo) Notes on the Textual Explanation of the Dharma Flower it says that “Preaching without being asked to”, in Tendai’s (T’ien T’ai) Textual Explanation of the Dharma Flower Sutra (Hokke Mongu), indicates that, at the beginning of the Chapter on Expedient Means, when the Buddha comes out of his perfect absorption into the Sutra on Implications Without Bounds (Muryōgi-kyō) and tells Sharihotsu (Shariputra), in a flow of words, about the boundless profundity of the Dharma – and then more briefly goes into the real aspect of all dharmas (shōhō jissō) and the ten ways in which dharmas make themselves apparent to our six senses [seeing, hearing, smelling, tasting, feeling, and imagining] (jūnyoze) – he also alludes to the omens in this and other worlds, as well as what can be put into words and what is beyond them. Again, the Buddha speaks about our objective realities (kyō) as belonging to the teachings that are derived from the recorded external events of Shākyamuni’s life and work which, like our own objective realities, can only be impermanent. Also, he speaks about the wisdom to understand our realities (chi) as being a part of the teachings of the original state (honmon). Both of these teachings are the root and source of the Dharma Flower Sutra (Hokke-kyō). Furthermore, these teachings are the culmination of the five periods of graded teachings, which led up to the exposition of the Dharma Flower – 1) the Flower Garland period (kegonji), 2) the period of the teachings of the individual vehicle (agonji), 3) the equally broad period (hōdō, vaipulya) in which both the doctrines of the individual and universal vehicles were taught, 4) the period in which the wisdom (hannya, prajña) sutras were instructed, and finally 5) the Dharma Flower period that lasted for eight years, including the sutra on the Buddha’s passing over to the extinction of nirvana, which was preached in a day and a night. This involves what our lives are all about and must not be taken lightly. What, in this explanation, is referred to as the root and source of the Dharma Flower Sutra (Hokke-kyō) and the culmination of the five periods of graded teachings that led up to the Dharma Flower is Nam Myōhō Renge Kyō.

All the deva (ten), dragons (ryū, nāga),

THE DHARMA FLOWER SUTRA SEEN THROUGH THE ORAL TRANSMISSION OF NICHIREN DAISHŌNIN

by Martin Bradley THE DHARMA FLOWER SUTRA SEEN THROUGH THE ORAL TRANSMISSION OF NICHIREN DAISHŌNIN

by Martin Bradley is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 2.5 Canada License. |